THE SOUTH CHINA SEA DISPUTE – WHERE TO FOR AUSTRALIA?

Isabella Jones, Mimi Chester and Emmanuel Choi

June 2nd, 2021

This edition of the GLSA’s ‘International Thinking’ Blog considers international law and the sea in the context of the South China Sea dispute and the relationship between China and Australia.

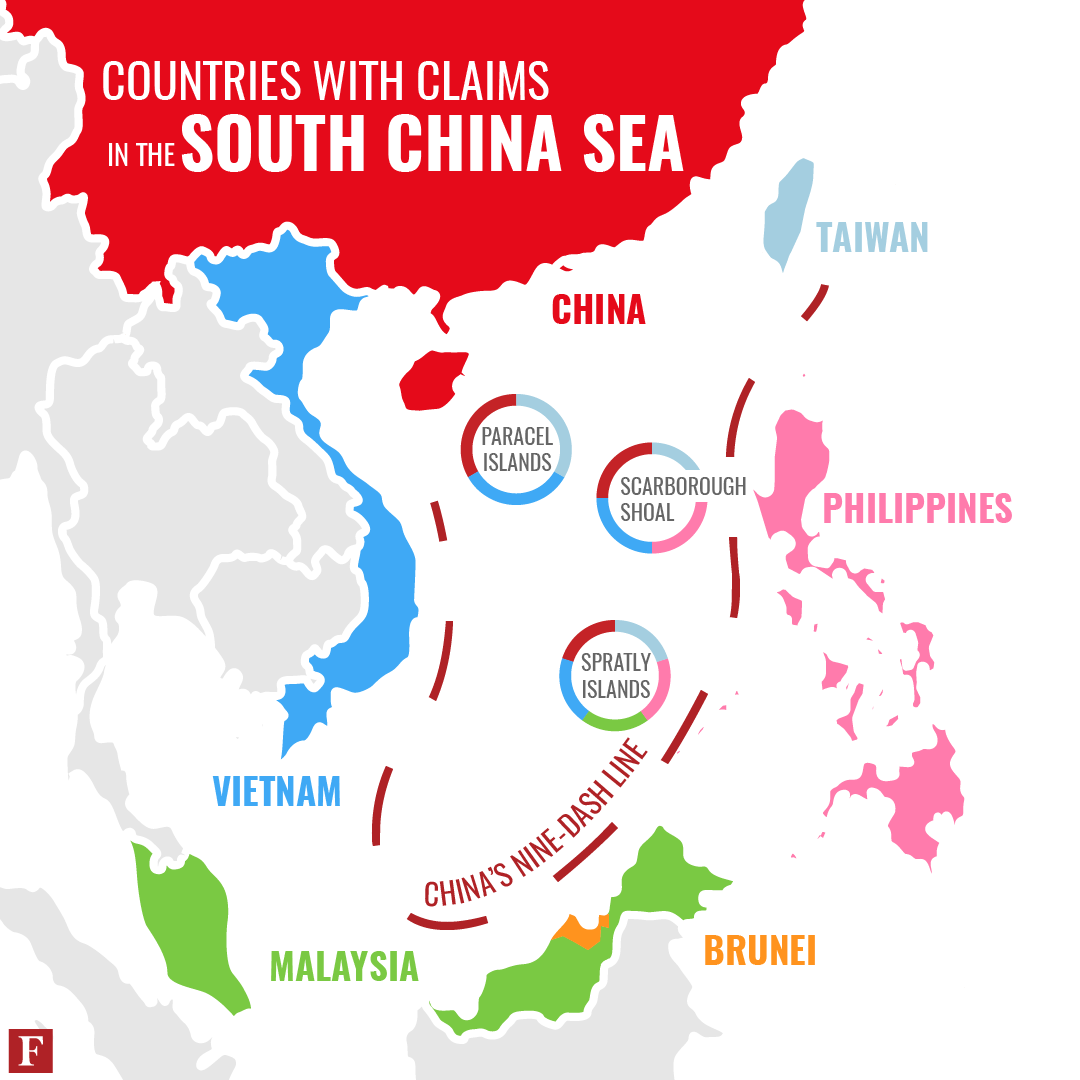

A site of great international contention, the South China Sea is a marginal sea, bordered by Brunei, Cambodia, China, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Taiwan, Thailand, and Vietnam (The Lowy Institute). The complex territory dispute is characterised by the region’s geographic and economic importance and by the weighty global consequences of the conflict (The Lowy Institute).

The key parties to the dispute are the regional states of China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Vietnam and Brunei. All states seek rights regarding navigation, fisheries, trade, and the vast natural resources in the region (The Asia Dialogue). The conflict is not a new one, but tensions in recent years have intensified, in no small part because of China’s growing global strength and assertiveness.

Parties have relied on international law for resolution. In 2013, the Philippines drew on their rights under UNCLOS and initiated proceedings against China in the Permanent Court of Arbitration for the Tribunal’s ruling, claiming that their sovereign right to maritime entitlements had been violated by China’s actions (PCA Case Nº 2013-19). China did not recognise and thus submit to the Tribunal’s jurisdiction on the matter, stating in 2014 that the matter regarded territorial sovereignty (Position Paper, Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China). Despite this, the Tribunal held that, per UNCLOS Article 9, Annex VII, a party’s non-participation does not prevent the arbitration from continuing, nor does it prevent the party from being bound by any award issued by the Tribunal (PCA Case Nº 2013-19, 3-4).

Want to know what law governs the sea? The starting point is the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

‘A Constitution for the Oceans’, UNCLOS combines traditional rules of the ocean, new legal concepts and regimes, and the framework for the further development of the law of the sea. It governs all aspects of ocean space, including delimitation, economic and commercial activities, environmental control and the settlement of disputes relating to ocean matters.

UNCLOS was opened for signature in 1982 and had 169 signatories as of 2016 (Britannica, Oxford). Global recognition and acquiescence have accorded UNCLOS the power of customary international law, thus binding states who have not signed and ratified the convention. China and Australia are parties to UNCLOS.

Despite the widely recognised success of UNCLOS, the Law of the Sea has unsolved issues, such as jurisdiction over natural resources, compensatory rights of landlocked states, preventing and combating marine pollution, chronic overfishing, and the preservation of biodiversity (Oxford).

The South China Sea Arbitration

In July 2016, the Tribunal’s judgment was released. In the ruling, the Tribunal expressly stated that the Tribunal was not asked to, and made no, ruling or judgment on claims of sovereignty; instead, the Tribunal was asked to resolve the parties’ disputes in regard to the source of maritime rights and entitlements in the South China Sea and the entitlement to maritime zones and features, and to resolve disputes regarding the lawfulness of China’s actions in the South China Sea (PCA Case Nº 2013-19, 1-3).

The Tribunal ruled in favour of the Philippines on nearly all of their submissions. However, the practical impact of the ruling is not cut-and-dried. The Tribunal’s considerations on future conduct of the parties note that the dispute lies not in either party’s intention to infringe the legal rights of the other, but in fundamentally different understandings of their respective rights under UNCLOS; nor is there any dispute by either party that the general obligations under UNCLOS provide guidance for their conduct in the matter (PCA Case Nº 2013-19, 468 [1198]). It is evident that UNCLOS has the capacity for conflicting interpretations. Another factor is the difficulty for international law enforcement mechanisms to find purchase on geopolitical disputes, especially when an interested party is a nation of great power.

China and the South China Sea

In response to the Tribunal’s ruling, China released a White Paper in July 2016 asserting its sovereignty over the region (White Paper, [123]) and its commitment to settling disputes through negotiation and consultation (White Paper, [121])

China’s claim to sovereignty over the South China Sea is significantly rooted in historical accounts dating back 2,000 years of discovery, control and regulation of the waterways (Paper Report, [4]). One particular narrative tells of the waterways being regulated by the Chinese Empires' tributary system, where vassal states gave tribute in exchange for the autonomy to conduct trade (Modern Diplomacy). Despite these vivid accounts, the Tribunal’s judgment stated that UNCLOS does not grant signatories with rights to claim sea areas based on historical legacy (PCA Case Nº 2013-19, 246). China’s ongoing conflation of rights to claim sea areas based on historical legacy is an example of the fundamentally different interpretation of rights under UNCLOS.

China’s 2019 White Paper states that the Philippines and China have got ‘back on track in addressing the South China Sea issue through friendly consultation’ (2019 Chinese Defence White Paper). However, the latest news about China and Philippines reports reactive militarization and a ‘war of words’ as China is reported to continue acting in violation of the Philippines’ maritime entitlements.

Australia’s role

Australia’s reputation as a world leader in marine law is premised on its expertise and willingness to cooperate regionally on marine conservation (Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment), not its expertise on maritime territory disputes. However, the urgency of the South China Sea conflict and Australia’s unique geographic and economic position in the dispute means that Australia has substantial interest in what happens in the waters. To navigate this dispute, Australia will likely draw on political and economic considerations as well as a rule-compliant interpretation of international law.

As a culturally Western yet geographically Eastern country, Australia’s official stance on the South China Sea dispute parallels that of long-time ally, the United States: both countries have endorsed a ‘rules-based order’ where the Philippines and China follow the norms of cooperative behaviour and abide by the final and binding ruling of the Permanent Court of Arbitration (DFAT, the Diplomat). Encouraging a system of order, not might, is a politically prudent position for a middle power country such as Australia.

Australia’s interest in the South China Sea is also economical due to its robust trade industry. The South China Sea sees an estimated one-third of global shipping (UNCTAD). Australia and its trading partners’ commercial interests will be largely affected by the freedom or lack thereof to navigate those international waters.

The conflict over the South China Sea is another brick in the wall of tension between Australia and China, two nations experiencing a current rift in their previously diplomatic relationship. While there has been no comment on specific details of Australian Defence Force operations, Australia has continued to transit the South China Sea (AFR), including participating in warship drills with the US (ABC News). This can be interpreted as solidarity with the US’s interpretation of the function of the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ), an interpretation markedly different from China’s. An EEZ is an area that extends to 200 nautical miles from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured (UNCLOS, Article 57) and in which the coastal State has specific rights, jurisdiction and duties as provided for in the Convention (UNCLOS, Article 56). While China has asserted that a state has the right to regulate military activity in its EEZ, the US draws on Article 58 of UNCLOS which provides that all States enjoy the freedoms of navigation and overflight in a State’s EEZ (the Lowy Institute).

In determining Australia’s ongoing response to conflict over the South China Sea, both economic and political issues have and will continue to have an impact. Just as we see tensions that have followed Australia’s call for an inquiry into the origins of COVID-19 and then the subsequent tariffs placed on Australia by China, actions that intensify the dispute over the South China Sea are likely to impact the currently fraught relationship between China and Australia. Australia’s likely path is to continue calling for compliance with international law norms and for a peaceful resolution that allows for continued economic stability.