TERRA NULLIUS: BEYOND MABO

JESSICA XU

August 26th, 2020

In Australia, terra nullius is a principle of international law that is most often associated with Mabo v Queensland (No 2).

It is a doctrine that has been used to justify a state’s claim of a territory by right of occupancy.[1]

Historical origins

Terra nullius is a Latin expression that roughly means ‘no man’s land’.

There has been debate about whether the concept is derived from the Roman law term res nullius. Res nullius, meaning ‘nobody’s thing’, is a principle that enabled things without an owner to be taken as property by anyone. [2]

Mabo v Queensland (No 2)

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/statelibraryqueensland/42294322084

Many Australian law students hear about Mabo long before they open their first law textbook. In any case, the MLS subject, Principles of Public Law, quickly introduces MLS students to its landmark decision, which overturned the terra nullius doctrine in relation to the British colonisation of Australia.

The legal fiction of terra nullius was basis of the British claim to Australia. This was famously rejected by the High Court of Australia in Mabo, thus paving the way for Australian native title.

Other historical terra nullius claims

While Mabo may be the case that Australians most often associate with terra nullius, the doctrine has existed all over the world. Some particularly interesting cases are as follows:

Svalbard

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Polar_bear_sign_Svalbard.jpg

Near the Arctic, the archipelago of Svalbard is so remote that it has never been settled by indigenous peoples.[3] However, since the 1600s, it had been used for activities such as hunting, trapping and research by people from various nations.[4] At the beginning of the twentieth century, after the discovery of coal deposits, mineral rights were claimed by countries and individuals from many countries.[5]

Norway was eventually granted sovereign control over Svalbard through the Spitsbergen Treaty, although the treaty had several unusual conditions. For example, it granted the 42 other signatories at the time free access to the territory, as well as the right of economic activities.[6] The treaty additionally prohibited the stationing of permanent military personnel or equipment on the archipelago,[7] and any taxation was required to benefit Svalbard only (and not Norway).[8]

US Guano Islands Act

The Guano Islands Act of 1856 is a federal law of the United States that enables American citizens to legally take possession of unclaimed islands that contained large deposits of bird (or bat) poop.[9] This was supposedly excellent fertiliser.[10]

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Navassa_island_riot_(1889)_(14775883312).jpg

The law had serious ramifications. While there was ostensibly a seven-point test for ascertaining the legality of a given land acquisition, the actual process was chaotic and inconsistent, resulting in legal confusion.[11] A territorial dispute arose when US explorers claimed an island that was, according to Haiti, under their jurisdiction.[12] The workers’ working conditions on the island were also horrendous, and five supervisors on the island killed in a protesting riot.[13]

The 1997 US case of US v. Warren confirmed that the Guano Islands still belonged to the US under US law.[14]

Principality of Sealand

The Principality of Sealand is a micronation that has existed since 1967 on an abandoned WWII British anti-aircraft platform in the North Sea, off the English coast of Suffolk.[15] Before being abandoned, it had once been occupied by up to 300 Royal Navy personnel, but it was later privately commandeered to set up a radio station to circumvent the UK Marine Broadcasting Offences Act of 1967.[16]

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/octal/173856263

The micronation has had a colourful history, with the stylisation of royal titles, the introduction of a coat of arms, constitution and passports, being a subject of a violent mercenary attack in 1978, as well as once becoming a symbol of anti-authority protests in the UK.

While the Principality of Sealand was originally in international waters (and thus outside UK jurisdiction), due to the UK extending its territorial waters in 1987, it is now in British territory.

Other claims

Other historical terra nullius claims include those of the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands, South Island of New Zealand, Eastern Greenland, Western Sahara, Canada, a strip of land along the Burkina Faso–Niger border, and the Scarborough Shoal in the South China Sea.

Current terra nullius territories

Terra nullius isn’t only a relic of the past, although its use is certainly quite rare nowadays. However, territories may still be left unclaimed for various reasons.

Antarctica – Marie Byrd Land

Marie Byrd Land is a remote portion of West Antarctica, named for the wife of Admiral Richard E. Byrd, who led the first exploratory flight over the area in 1929.[17] Most of the uninhabitable territory has not been claimed by any country. It is the largest single unclaimed territory on Earth.[18]

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/gsfc/6260499963

The region boasts one of the harshest climates on the planet, and it is so inaccessible and rough that no country has sought to claim the area. It no longer has any research bases, with the former Soviet Russkaya Station closing in 1990, and the US Byrd Station closing in 2005.[19]

In contrast, seven countries have currently made territorial claims in the rest of Antarctica, including Argentina, Australia, Chile, France, New Zealand, Norway and the United Kingdom.

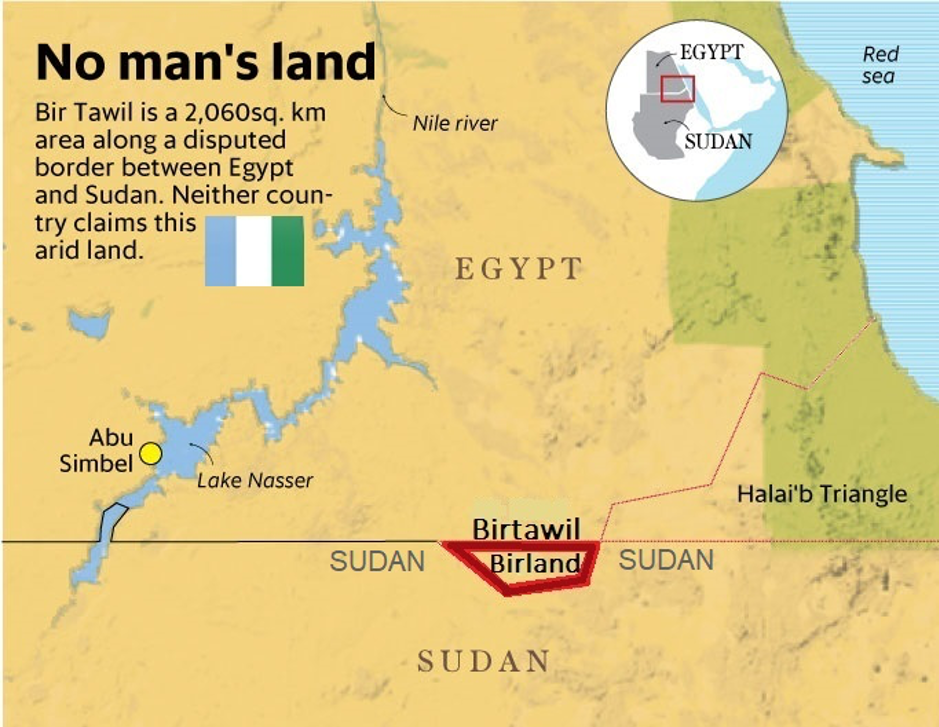

Bir Tawil

Bir Tawil is a landlocked area on the border of Egypt and Sudan.[20] It isn’t an insignificant amount of land – its size of around 2060 km² means that it is larger than twenty-seven countries.[21] However, there is nothing there aside from desert, as well as a number of small settlements.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bir_Tawil-Map.jpg

However, and perhaps more importantly, Bir Tawil is situated near a larger area of land called the Hala’ib triangle, which has rich soil and borders the coast.[22] A long-standing dispute exists between the two countries over the Hala’ib triangle, and of the two differing boundaries drawn during the colonial era, one favours Egypt and the other favours Sudan.[23] Either way, the country that acquires Bir Tawil will lose the Hala’ib triangle.[24]

Bir Tawil is considered by the Ababda tribe as their native homeland.[25]

Source: https://www.flickr.com/photos/orhamilton/25880678250

Private claims

In 2004, American-born micronationalist Travis McHenry styled himself the Grand Duke of Westarctica in his attempt to lay claim to the Antarctic Marie Byrd Land.[26] In a similar vein, several non-state parties have attempted to claim Bir Tawil, including Virginian farmer Jeremiah Heaton, who in 2014 tried to found the ‘Kingdom of North Sudan’ in order to make his seven-year-old daughter a ‘princess’.[27] Unsurprisingly, none of these claims to sovereignty have been recognised by the UN.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_the_Kingdom_of_North_Sudan.svg

But is the doctrine of terra nullius limited to claims by nation states? Can anyone, including you and me, claim private ownership of terra nullius territory?

Not according to Australian jurisprudence. In 2016, as part of a dispute concerning two islands in the Coral Sea, the Full Court of the Federal Court of Australia rejected the argument that there is a rule of international law allowing an individual to acquire proprietary rights over terra nullius which nation states must recognise.[28] (A special leave application to appeal the decision was refused by the High Court.[29])

Terra nullius and space

There are many reasons why a country may want to claim an astronomical object – such as for mining, weapons positioning, or weapons testing. However, the terra nullius doctrine appears to be limited to Earth, per the common heritage of mankind principle.

Source: https://unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html

The Outer Space Treaty (formally, the Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies) entered into force on October 10, 1967.[30] It provides the basic legal framework of international space law.

Notably, Article II affirms that:

Outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, is not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.

This article, along with language throughout the Outer Space Treaty which emphasises its communal and cooperative intent (such as ‘the common interest of all mankind’, ‘free for exploration and use’, ‘free access to all areas of celestial bodies’ and so on) strongly suggest that the terra nullius doctrine is only appropriate on our own planet.

(However, as with all treaties, there are many countries which are not parties, and some which have signed but not yet completed ratification.)

Other zones that similarly fall under international jurisdiction per the common heritage principle include international airspace, international waters and the international seabed.

Terra nullius nowadays

The terra nullius doctrine generally appears to be relegated to the past (or at least to quirky stories about micronations).

There are few existing modern applications or, with the backdrop of today’s international law, particular economic incentives to enliven the principle in the future.

However, the effects of its historical use continue to be deeply felt, particularly by Indigenous peoples displaced and disconnected from their traditional lands. This is compounded by the Australian ‘history wars’, a public debate over nature of Indigenous dispossession that has been ongoing for decades.

[1] https://www.oxfordreference.com/view/10.1093/acref/9780195557558.001.0001/acref-9780195557558-e-3278

[2] https://www.jstor.org/stable/40646121?seq=1

[3] https://www.traveller.com.au/svalbard-norway--life-in-the-deepfreeze-gtlkzi

[4] https://svalbardmuseum.no/en/kultur-og-historie/svalbardtraktaten/

[5] https://www.britannica.com/place/Svalbard

[6] https://www.traveller.com.au/svalbard-norway--life-in-the-deepfreeze-gtlkzi; https://www.spitsbergen-svalbard.com/spitsbergen-information/history/the-spitsbergentreaty.html

[7] https://www.spitsbergen-svalbard.com/spitsbergen-information/history/the-spitsbergentreaty.html

[8] https://svalbardmuseum.no/en/kultur-og-historie/svalbardtraktaten/

[9] https://www.vox.com/2014/7/31/5951731/bird-shit-imperialism

[10] https://ushistoryscene.com/article/guano-islands-bird-turds/

[11] https://www.vox.com/2014/7/31/5951731/bird-shit-imperialism

[12] https://ushistoryscene.com/article/guano-islands-bird-turds/

[13] https://www.vox.com/2014/7/31/5951731/bird-shit-imperialism

[14] https://www.vox.com/2014/7/31/5951731/bird-shit-imperialism

[15] http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20200706-sealand-a-peculiar-nation-off-englands-coast

[16] http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20200706-sealand-a-peculiar-nation-off-englands-coast

[17] https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/marie-byrd-land

[18] https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/marie-byrd-land

[19] https://en.wikivoyage.org/wiki/West_Antarctica

[20] https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/bir-tawil-1

[21] https://www.atlasobscura.com/places/bir-tawil-1; https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/the-smallest-countries-in-the-world-by-total-land-area.html

[22] https://www.youngpioneertours.com/strange-tale-bir-tawil/

[23] https://www.youngpioneertours.com/strange-tale-bir-tawil/

[24] https://www.youngpioneertours.com/strange-tale-bir-tawil/

[25] https://www.youngpioneertours.com/strange-tale-bir-tawil/

[26] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-04-30/the-weird-wild-world-of-micronations-where-anybody-can-be-king

[27] https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3077444/I-m-real-life-Elsa-Devoted-dad-founds-Kingdom-North-Sudan-unclaimed-land-African-desert-make-daughter-proper-princess.html

[28] Ure v The Commonwealth of Australia [2016] FCAFC 8 [accessed at http://www8.austlii.edu.au/cgi-bin/viewdoc/au/cases/cth/FCAFC/2016/8.html]

[29] BUCKLAND, Andrew; LOUGHTON, Gavin; BOYLE, Liam and and, others. Right of individuals to acquire proprietary rights over terra nullius under international law [online]. LITIGATION NOTES, No. 27, 17 November 2017: 52-53. Availability: <https://search.informit.com.au/fullText;dn=20175238;res=AGISPT> ISSN: 1329-458X.

[30] https://unoosa.org/oosa/en/ourwork/spacelaw/treaties/introouterspacetreaty.html